Antique stores and thrift shops are full of ghosts—not those seen in the shadows at night, but actual images imprinted on brittle paper and fading ink. I’m forever drawn to their remnants, as my husband can attest, easily spending an hour sorting through vintage postcards or abandoned photographs. I can’t help but be amused by a personal note written more than 100 years ago, or charmed by random strangers dressed in old-fashioned garb. These fragments whisper of lives once lived, and I listen.

While the identities of those in the photos often remain mysterious, their images are compelling. They connect us to the past in an inexplicable, visceral way—and we need that connection even more in these uncertain times. It’s proof that our ancestors, whether actual or adopted, endured and even thrived through challenging circumstances. In some cases, we may never know their names, but in these relics, they persist—proof that even in the dimmest corners of history, life refuses to be forgotten.

Instant Ancestors

Sifting through stacks of discarded photographs, I always find myself wondering, “How did they end up here, untethered from the families they once belonged to? Were they truly forgotten, or did no one remain to mourn them? Could my own family’s photographs also be lost, languishing in a random thrift store somewhere?”

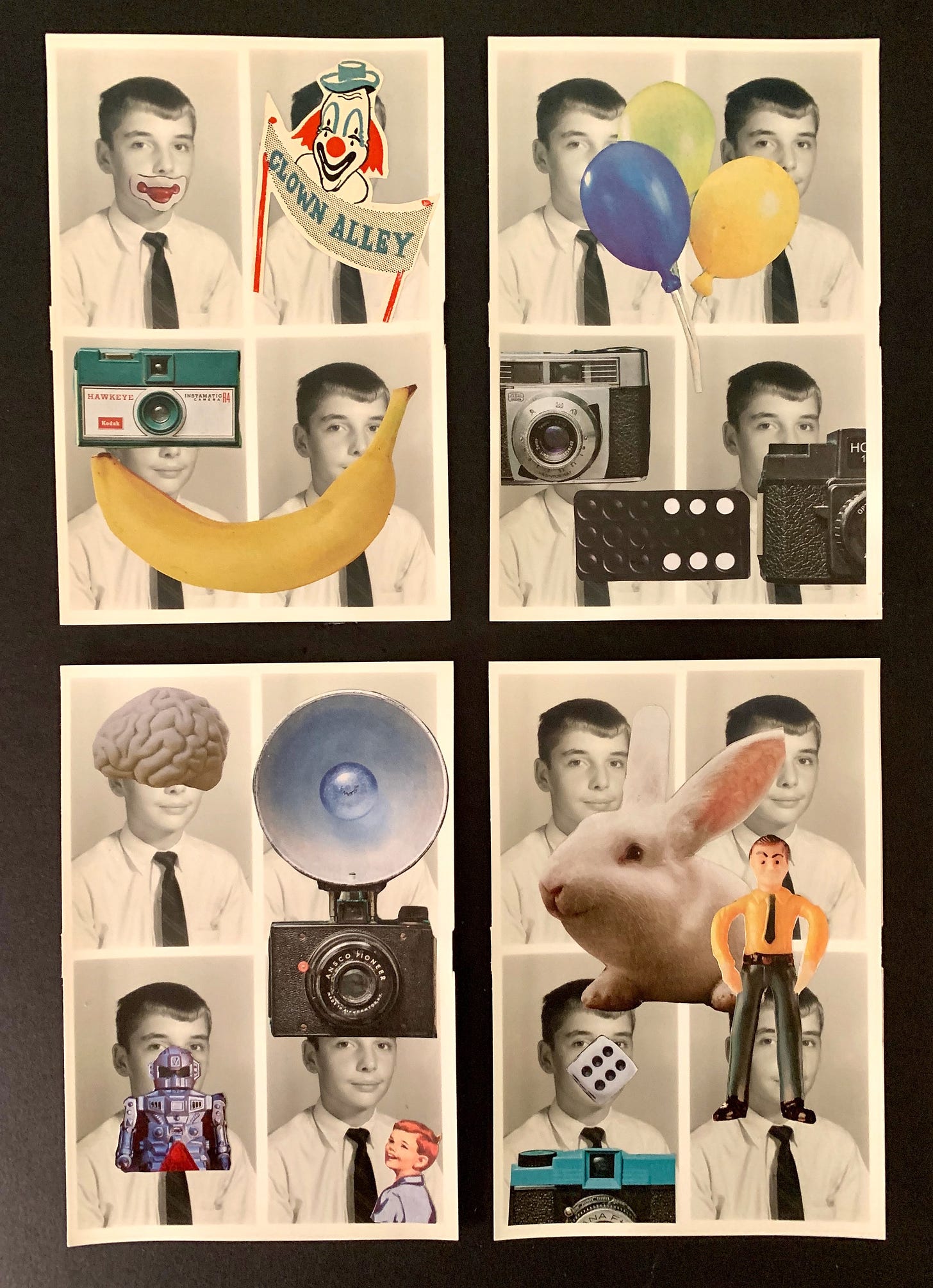

Perhaps that’s why Grimrose Manor has become a refuge for these lost souls—strangers too haunting to abandon, their likenesses too compelling to ignore. We call them our “instant ancestors,” the silent specters who watch from antique frames. I sometimes even incorporate found photos in my collage art.

The Gift

Not long ago, a local artist I admire (who, I might add, has never even been to our house) mentioned that she had an old photo album to give me. Her friend had picked it up second-hand a few hours away and for some reason she thought of me. I was delighted and intrigued at the prospect of using an old photo or two in a new collage. But the idea quickly faded when I finally had the album in my hands.

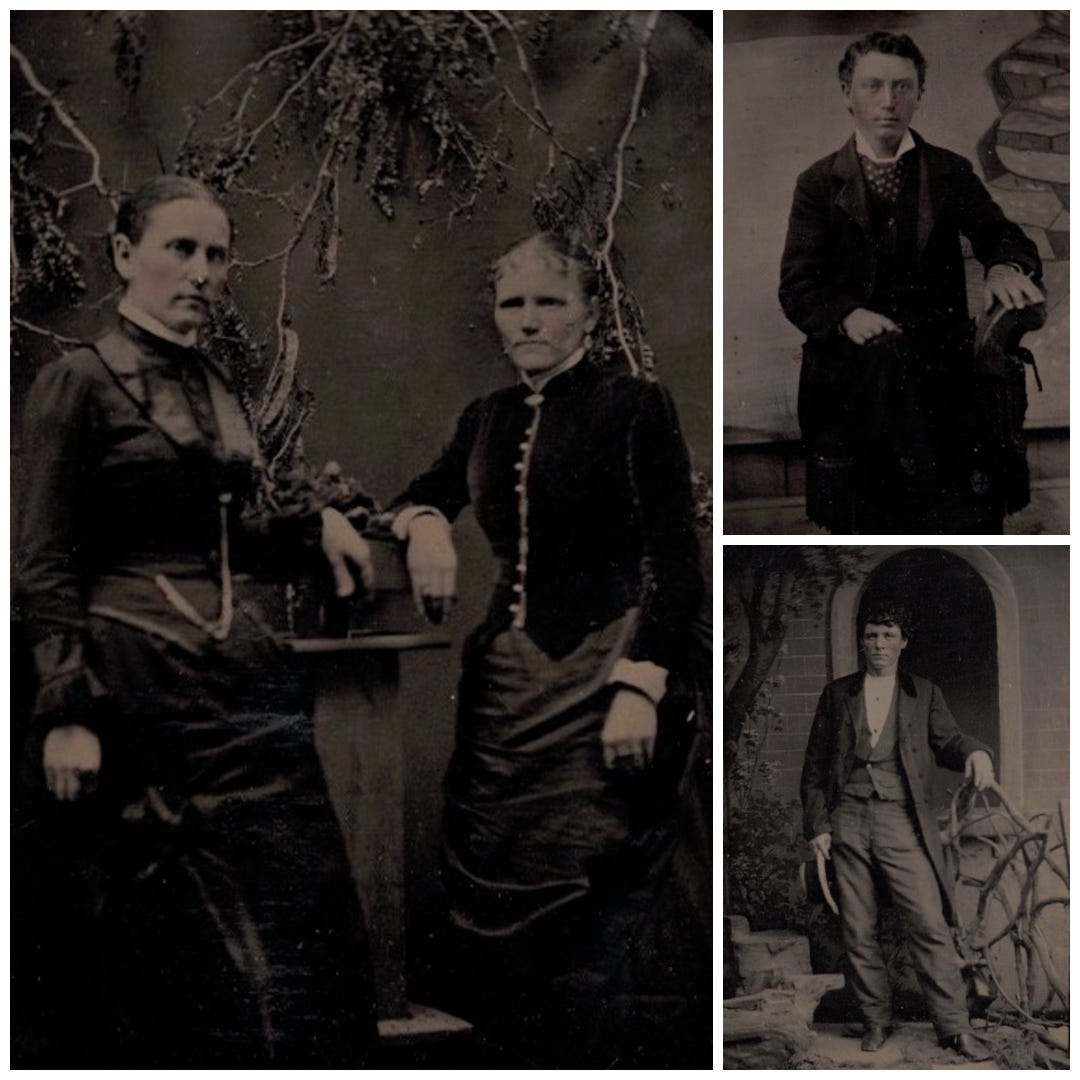

In my head, I had envisioned a random assortment of unlabeled black-and-white pictures, but this was a veritable relic. It had an ornate cover, thick gilded edges, a deteriorating leather spine, and broken brass latch. Inside were 33 antique photos, only 7 of which didn’t have some kind of name or identifier. How could I bring myself to dismantle such a thing? A true mystery had fallen into my lap.

Some of the images appeared to be tintypes. (To see the tintype process in action, watch this brief video featuring Mark Osterman, a former colleague from my time at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y.)

Many of the other images were carte-de-visite (or CDV)—small, card-mounted albumen prints that were popular in the mid-1800s. (These were later followed by a larger format known as “cabinet cards.”)

In all, there were 14 different surnames included in the album but several repeated: Crane (8), Lindsay (4), Fulton (3), and Chick (3).

After some dogged online investigating, I was able to positively identify a Crane family from the 1860s whose two daughters had married a Lindsay and a Fulton. Success!

I also discovered that the Crane parents, two siblings, and several of the Lindsays were buried in Grafton, Jersey County, Illinois—about 40 miles from St. Louis, Missouri, where some of the other Crane siblings were buried.

At this point, I had hopes of finding a grateful descendent who might want the album, but this tack proved unsuccessful. Instead, I was delighted to find that the Jersey County Historical Society has a materials donation form. I messaged and they warmly responded that they would love to give the album a home.

Of course, in rescuing these “instant ancestors,” I’ve bound myself to them in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Their faces have become familiar, their presence undeniable, so I scanned the whole thing. I also plan to upload the identified photos to various online archives where their names will be whispered once more into the digital ether.

Patron Saints of Lost Photos

For more intrigue of this nature, the following admirable folks have made it their missions to rescue and reunite found photos with families, descendants, or historical societies:

David Gutenmacher started the Museum of Lost Memories in 2020 and often uses Patreon and Instagram to crowdsource solutions.

Content creator and TV host Dan Rodo (aka Danocracy) started a series in 2020 called Shot and Forgot and continues detailing his sleuthing on video.

Kate Kelley started the Photo Angel Project in 2021, shares her finds in a Facebook group, and even appeared on NBC’s TODAY show.

For Fanciful Reading

If found photos inspire your brain to make up stories about the lives represented, you’re in great company. We recommend the following fictions for more delight:

Instant Ancestors: Preposterous Tales Sprung from a Shoebox by Russell Shuler

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued from the Past by Ransom Riggs (author of the Peculiar Children series—itself inspired by found photos)

I recently inherited some family photos - some no-so-old which feel less like "must -keeps" - Part of me wants to scan them and then dispose of the originals to not have to worry about storing or keeping track of them from now onward. But discarding them also feels "wrong." Perhaps I'll end up saving them to hand off to my favorite collage artist!

I love the term "instant ancestors." I have definitely felt the same pull when I encounter old photos in thrift stores or antique shops.