This week, Grimrose Manor is pleased to present an article by guest contributor Dr. Gabriella V. Smith, aka Gabriella the Garden Sage. She runs the Power Plant in Southwest Virginia, where she holds events and workshops, and offers virtual garden consultations. As a garden designer with a Ph.D. in Sociology, Gabriella is perfectly suited to illuminate us on this topic. Enjoy!

Love it or hate it, Valentine’s Day is on the horizon. [At Grimrose Manor, we’re more into “Valoween,” but that’s a different topic altogether.]

This commercial holiday is the most profitable time of the year for the floral industry, with red roses dominating sales. In my retail florist days, I tried to steer people to more creative solutions—ones that would last longer, look better, or came into the wholesaler fresher. I was even trying to save folks from the incredible wholesale markup on roses this time of year. (Pro tip: Roses are least expensive in late-summer or early-fall, before growers need to stop harvesting to get those V-day long stems).

Alas, I was often unsuccessful, even being told that a gift of anything other than a dozen red roses would be interpreted as “I DON’T LOVE YOU.” The association of red roses with romantic love is widely known, if too stringently observed. But floral consumers in the past availed themselves of a huge range of plant materials to communicate nuanced messages.

Flower Fluency

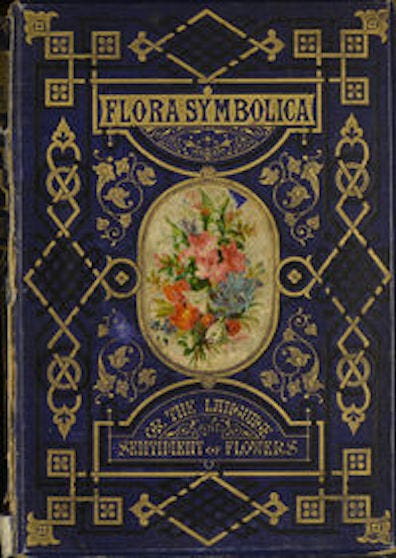

Floriography, or the “language of flowers” began its rise to popularity in France with the 1819 publication of Charlotte de la Tour’s Le Langage des Fleurs and reached its nadir in Victorian Britain. The fashion for communicating via floriography blossomed among the newly prosperous middle classes, rooted in economic and gender dynamics. First, purchasing cut flowers was an attainable luxury for this newly enriched class. Second, floral arranging and horticulture was an acceptably chaste and respectable diversion for women with freshly acquired leisure time.

Floral dictionaries were popular gifts and a staple of many middle-class households, outlining the meanings of plants and flowers, even down to specific colors. These symbolic manuals allowed coded messages to be sent through a cleverly crafted bouquet. However, complications inevitably arose if the sender and recipient weren’t using the same floriography manual, as new floral directories proliferated without coherent symbolic meanings. To further complicate matters, florists often invented connotations for the glut of brand-new varieties coming from contemporary breeders or plant hunters.

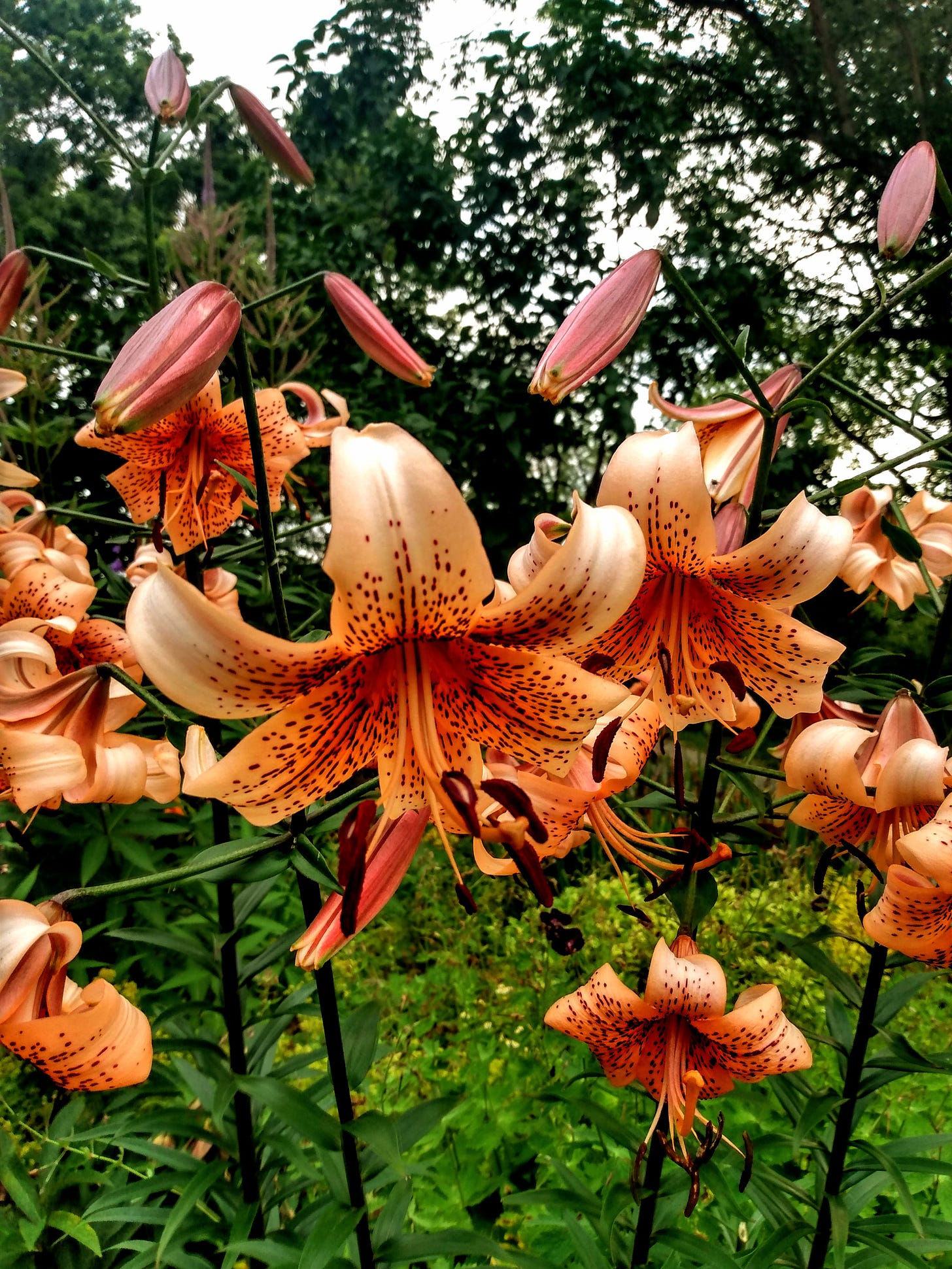

While today’s Valentine bouquets tend to communicate love and affection, Victorian floriography guides allowed a wider range of expression, including the passionate, caustic, or downright insulting. As the gospel of Luke (or Monty Python’s The Life of Brian) advises, “consider the lily … .” White lilies have a long association with the Virgin Mary, while orange lilies could mean “You are proud” but also “I hate you.” Orange lilies are a particular favorite of mine, especially “African Queen” and “Tiger Babies.” One would imagine my yard could be a giant middle finger to passing Victorians.

The symbolic meaning of some flowers do have roots in the more distant past than the 19th century. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, act 4, scene 5, Ophelia bestows rue (ruta graveolens) on Hamlet and keeps some for herself. Rue is a particularly bitter herb and has a long association with sorrow and disappointment, its name being synonymous with regret. Victorians incorporated such known associations and built upon them. Jessica Roux notes in her Floriography that “most often, rue was sent, not to express regret on the part of the sender, but as a warning or threat, as in ‘You’ll regret what you’ve done.’” As someone who has suffered horribly from photosensitivity burns after contact with rue plants, this rings particularly true.

Best Death Wishes

Victorians were often considered somewhat obsessed with death. From establishing park-like cemeteries, to popularizing post-mortem photography, to elaborate mourning dress etiquette, one could credit the Victorians with a profoundly morbid sensibility. Though, in truth, my middle-aged Goth heart thanks them. It isn’t a shock to find that flowers were also associated not only with sending messages of condolence (chrysanthemums), but that so many could be used to communicate death.

While there are as many as 100 species in the genus papaver, it’s opium poppies, Papaver somniferum, that made frequent appearances in various floriography guides. Unsurprisingly, opium poppy is commonly interpreted as “eternal slumber” or “unending sleep,” aka death, due to its long association with narcotics and use as a poison. Given its difficulty as a cut flower, I hope not many death wishes were sent using this method.

Deadly nightshade is dangerous to touch due to its levels of toxicity, so including it in a bouquet seems unwise if you didn’t literally wish death upon the recipient. However, various guides indicate its symbolic meaning is “silence.” With sufficient contact, such silence could be permanent. Hemlock, conium maculatum, is another plant I would hesitate to incorporate into a bouquet, however its inclusion also meant death. Given hemlock’s close resemblance to Queen Anne’s Lace, daucus carota, meaning “sanctuary,” one would hope the sender and recipient were adept botanists.

Season to Taste

While the fashion for floriography wilted following World War I, it is experiencing a resurgence thanks to greater interest in gardening and all things witchy and witch adjacent. One of my favorite recent guides is Jessica Roux’s Floriography (2020), featuring beautiful illustrations and helpful bouquet recipes for various messages.

Needing to warn someone off? She suggests a combination of begonia for “warning,” oleander for “caution,” lavender for “distrust,” and foxglove for “secrecy,” tied with a red band.

Leaving a relationship on less-than-favorable terms? Combine petunias for “anger and resentment,” tansy for “hostility,” wormwood for “bitterness,” thistle for “misanthropy,” and datura for “deceitful charms.” Datura’s poisonous, too, so you could always hope they go in for a deep sniff.

Perhaps the true magic of floriography lies not in its rigid rules, but in its deliciously wicked potential for subversion. Why settle for the tired, mass-produced language of supermarket roses when you could craft a floral proclamation fit for a gothic novel? So, this Valentine’s Day—or Valoween, if you prefer—consider a bouquet that speaks in thorns as well as petals. After all, love is fleeting, but a well-placed botanical hex? That lingers.

I've learned about flowers as symbols on gravestones but hadn't made the connection with how they might be used to communicate messages in bouquets. Thanks for the guide.