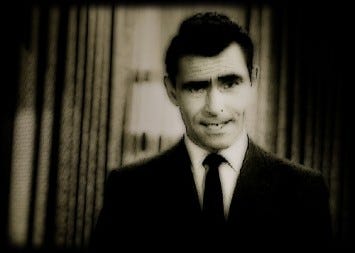

June 28, 2025, marks 50 years since the passing of Rod Serling—a man whose voice could soothe or chill, whose typewriter conjured monsters and morality with equal precision, and whose vision opened doors not just to another dimension, but to ourselves.

In the half-century since his death, Rod Serling has remained curiously alive—his name spoken with a certain awe (certainly here at Grimrose Manor), his shadow cast long across screens and scripts, his influence as sharp as ever. You can feel it in every anthology show that traffics in twist endings, in every black mirror that dares to reflect us. But none have equaled him. None have spoken with his strange, humane thunder.

Growing up, I didn’t know much about Serling or The Twilight Zone other than a few cultural references and of course imitations of Serling’s peculiar speech patterns. The show’s five-year run was over well before I was born. Several years ago during some holiday weekend, one of the cable channels—most likely SyFy—offered a Twilight Zone marathon. I recorded every episode and watched them religiously over the next few weeks. I was hooked. I was in awe. And I had never been a science fiction fan. Slowly, I learned Serling’s style and loved to guess if Serling himself wrote the episode I was watching. After the first dozen or so episodes, I was right more often than not.

Serling didn’t merely create The Twilight Zone. He built it like a moral clockwork and then dared us to listen to it tick. With one foot in the uncanny and the other in the urgent, he used science fiction not as escape, but as confrontation. He wrote of aliens and ventriloquist dummies and talking dolls, yes, but also of fear, conformity, cruelty, vanity, and our terrifying capacity to dehumanize one another.

“The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” didn’t need a spaceship to land for the real horror to begin. Just suspicion. Just paranoia. Just a few flickering lights and the unspoken knowledge that we are always just one crisis away from turning on our neighbors. That episode, like so many of Serling’s, remains agonizingly relevant—our towns, our social media feeds, still primed for pitchforks.

Serling understood masks. Yes, the grotesque ones worn in the New Orleans of “The Masks,” but also the kind we wear to conceal our greed, our resentment, our frailty. He knew how much ugliness we assign to others to avoid facing our own. In “Eye of the Beholder,” beauty becomes a weapon. In “It’s a Good Life,” power is made monstrous by childish whim. And in “The Dummy,” identity itself comes undone with actor and puppet trading places in a dance of dread.

And then there’s “To Serve Man,” that devastating sleight of hand that takes three words and flips them from promise to peril. Or “Living Doll,” which reminds us that the preternatural doesn’t require special effects. Sometimes, a voice in the dark is enough. Serling didn’t write those two episodes, but they bore his fingerprints: irony sharpened into something surgical.

Serling was ahead of his time, and often at odds with it. A World War II paratrooper turned playwright, he fought networks and censors alike to tell stories that mattered. When they balked at scripts dealing with racism or anti-Semitism, he cloaked his commentary in the stars and shadows of genre. The result? Subversion through storytelling. He smuggled truth past the guards of the era’s polite television by dressing it in the garb of fiction.

Grimrose Manor, a place not unfamiliar with eerie ambiance or moral rot cloaked in velvet, feels a certain kinship with Serling’s sensibilities. We, too, believe that stories should haunt you a little. That the darkness can be instructive. That the dead have something to teach us, and maybe, just maybe, they’ve been listening all along.

Rod Serling died at just 50, his heart overworked, his lungs scarred from too many cigarettes and too much worry. But in that short time, he created a body of work that still breathes. His narration, that dry, deliberate cadence, is practically scripture to those of us who walk between shadow and substance. He didn’t simply write television, he altered what it could do.

Fifty years gone, and yet The Twilight Zone persists‚ both in the sense of reruns and reboots, but also as metaphor, as warning, as mirror. Serling’s legacy is not nostalgia. It is prophecy. Because every time we look around and think, “This doesn’t feel real,” we’re reminded: Serling got there first.

He told us stories about ourselves, dressed in just enough fiction to slip past our defenses. And for that, he doesn’t rest in peace. He lingers.

Right … here.