Carnton—a historic site located in Franklin, Tenn., about 25 miles south of downtown Nashville—stands as a solemn reminder of our nation’s past, particularly its role during the Civil War. (See also: our statement about Civil War coverage.) Once a thriving home and farm thanks to the labor of enslaved people, the property was owned by the McGavock family. Then, on the fateful night of Nov. 30, 1864, it became a field hospital during and after the Battle of Franklin.

The battle was one of the bloodiest encounters of the Civil War and left the area scarred with unimaginable losses. Carnton's legacy is now forever intertwined with the stories of the wounded and dying soldiers who were treated within its walls. Today, this grand mansion and its surrounding grounds serve as a haunting reminder of the devastation of war and the resilience of those who lived through it.

As you approach the imposing Greek Revival home, Carnton’s stately columns and quiet presence offer a glimpse into the antebellum South. The well-preserved mansion retains much of its original structure, including the iconic sweeping porches that once served as operating spaces for the surgeons tending to the wounded. Visitors are immediately struck by the sense of history that permeates the air, from the expansive grounds to the period interiors, meticulously recreated and including a handful of items original to the house. (Not shown, as photos were prohibited inside.)

Historically called “Carnton,” the moniker, “Plantation,” was added in the early 1990s and then removed in 2017. (According to our guide, Chelsea, the distinction is that Carnton was a self-sustaining farm growing multiple crops, whereas plantations grow a single cash-crop for mass production.)

We wondered if the change might be a bid to distance its history from that of slavery—as of the 1860 Census, there were 44 enslaved people on the property—but the interpretive narrative doesn’t shy away from slavery’s reality. Slave quarters are a standard inclusion on tours, along with the stories of several enslaved people, and a specialty tour is offered on the topic.

During our 90-minute guided tour, visitors were transported back in time, learning about the McGavock family’s role in caring for the soldiers who flooded their home in the wake of the battle. Per the aforementioned 1860 Census, the whole town of Franklin had a population of roughly 750 and it was about that same number of soldiers who were treated—with many dying—at Carnton.

The tour gives an intimate look at the home’s transformation during that critical time, the medical practices of the era, and the personal sacrifices made by those tending to the injured, including the children of the house. The blood-stained floorboards still bear witness to the make-shift hospital. Speculation about one unusually shaped stain is that the blood had pooled there around the surgeon’s shoes.

With such great tragedy and suffering, one might wonder what still haunts these grounds. While some purport to have seen spirits on the property, our guide denied having witnessed any.

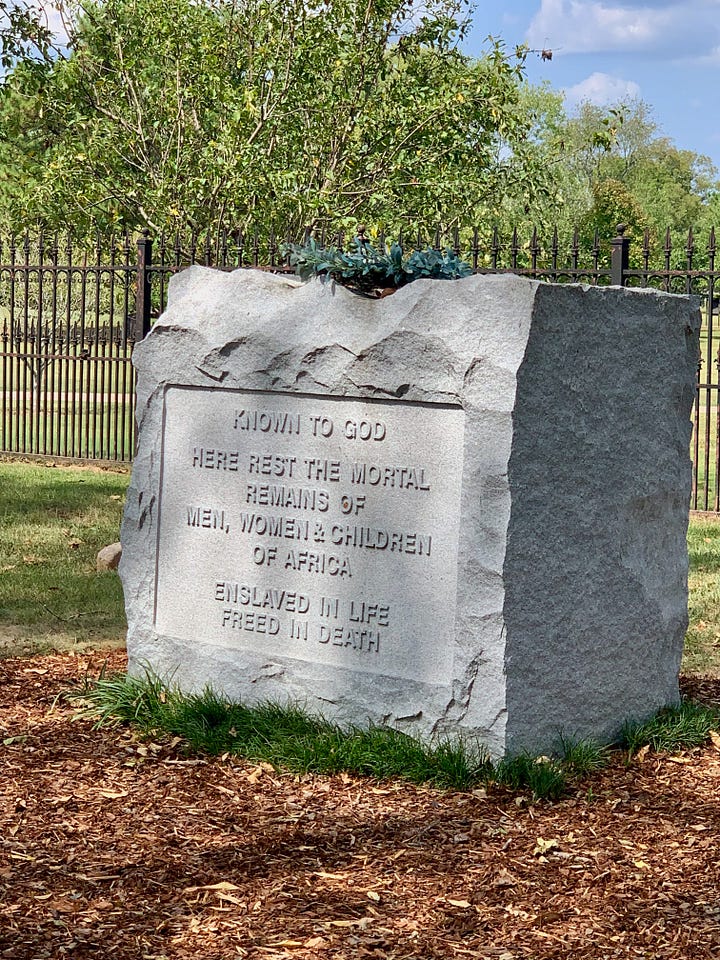

Outside—beyond the family’s private cemetery and a marker for the mostly unidentified slaves buried nearby—lies McGavock Confederate Cemetery, our nation’s largest Confederate gravesite.

Originally buried nearer the battle field, nearly 1,500 fallen soldiers were exhumed and re-interred here in 1866—a process that’s difficult to fathom. Organized around 10 state monuments, roughly 780 bodies were identified, but many are simply marked as unknown.

While a visit to Carnton is indeed sobering—providing a vivid reminder of the harsh reality of what war brings—it also creates a deeply emotional connection to the past, and is well worth the visit.